Forthcoming by Asemana Books (April 3, 2026)

هیجانالوطن

میرزا فتحالله قدسی کرمانی (فواد کرمانی)

تصحیح انتقادی و معرفی:

مهدی گنجوی و علی مظفری سیرجانی

همراه با مقالاتی درباره زیست و روزگار فواد کرمانی و میراث گفتمان ازلی در جنبش مشروطه از

منوچهر بختیاری

علی مظفری سیرجانی

و یادداشتی از

مهران راد

گفتمانِ ازلی، که پس از مرگِ باب و در تقابل و رقابت با آیینِ بهائی شکل گرفت، صرفاً یک جنبشِ دینی نبود. ازلیان کوشیدند در درونِ سنتِ اسلامی ـ ایرانی، قرائتی باطنی، ضداستبدادی و تحولخواه پدید آورند؛ قرائتی که از یکسو بازپردازیِ سنتِ اسلامی را مطالبه میکرد و از سوی دیگر، با افزودن بر کانونهای متنی و جابهجاییِ مرجعیت، در پیِ دگرگونسازیِ بنیانهای اقتدارِ دینی بود. از این حیث، ازلیان در موقعیتی میانجی قرار داشتند و میانِ سه قلمرو در نوسان بودند: سنتِ عرفانی و باطنی، عقلانیتِ مدرن، و اندیشهٔ رهایی.

ازلیان میدانستند که بیان آشکار عقایدشان در ایران قاجاری به بهای جان تمام میشود. از همینرو، نوشتارشان چهرهای دوگانه یافت: سطحی آشکار و سطحی باطنی. در ظاهر، نصیحت میگفتند و اصلاح اخلاق مردمان را خواستار بودند.اما، در باطن، نقد مرجعیت و انحلال نهاد روحانیت، نقد شریعت اسلامی و دعوت به شریعتی بازپرداخت شده، و دعوت به مبارزه با قاجار را دنبال میکردند.

این دوگانگی در آثارِ فؤادِ کرمانی، بهویژه در هیجانالوطن، نمودِ روشنی دارد. زبانِ شعر در نگاهِ نخست، زبانی ملی و خطابی است، اما در سطحی عمیقتر، با اندیشه و جهانبینیِ جنبشِ بابی و دلالتهای اجتماعی و سیاسیِ آن واردِ گفتوگو میشود. از همینرو، اگر متن با نگاهی رمزخوان و آگاه به اشاراتِ ازلی و محاسباتِ عددیِ کلمات خوانده نشود، ممکن است صرفاً بهعنوان متنی سکولار یا اصلاحطلبِ شیعیِ مشروطهخواه فهم شود و لایههای متمایزِ فکریِ آن نادیده بماند. نادیدهماندنی که آفت بسی خوانشها از عقاید ازلیها و تفسیرگریهای مشروطه ایرانی است.

فؤاد، شاعرِ مشروطۀ کرمان است و از آنجا که چهرههایی چون میرزا آقاخان، شیخ احمد روحی، میرزا رضا، مجدالاسلام و ناظمالاسلام از این شهر برخاستهاند، مطالعهٔ شعرِ او بهمنزلۀ گشودنِ دریچهای برای شناختِ یکی از کانونهای مهمِ مشروطۀ ایرانی، یعنی کرمان، تلقی میشود. کرمانِ روزگارِ فؤاد میدانِ تلاقیِ آرا و عقاید گوناگون بود و بهدرستی میتوان آن را کارگاهی پرجوشوخروش از اندیشههای الهیاتی دانست؛ شهری که در آن، شیخیان، اسماعیلیان، نعمتاللهیان، بهائیان و ازلیان حضور داشتند و در پیِ مراوده و نزاع بر سرِ نسبتِ امرِ کهن و امرِ نو، بسیاری از مفاهیمِ آیندهٔ ایران را در همین سپهر صورتبندی کردند.

کتاب فعلی، افزون بر آنکه تصحیحی انتقادی و دقیق از این اثر به دست میدهد، کوششی آگاهانه برای بازاندیشی در برخی روایتهای تثبیتشده از مشروطیت ایران نیز بهشمار میآید. اثر حاضر با فراهمآوردن متنِ تصحیحشده و معرفیِ زمینههای تاریخی، فکری و اجتماعیِ آن، میکوشد این متن را از جایگاهِ صرفاً ادبی یا محلی بیرون بکشد و در دلِ منازعاتِ گفتمانیِ عصر مشروطه بنشاند. در کنارِ تصحیح و معرفی، مجموعهای از مقالهها نیز آمده است که هدفِ آنها نه صرفاً شرح و توضیح، بلکه مداخلهای تحلیلی در فهمِ گفتمان مشروطیت در ایران است؛ مداخلهای که میکوشد از مرکزیتِ روایتهای تهران وتبریز محور فاصله بگیرد و نقشِ ایالات، بهویژه کرمان، را در شکلگیری، تداوم و تنوعِ این جنبش برجسته سازد.

The Homeland’s Uprising Spirit

By

Mirza Fatolah Qudsi Kermani (Foad Kermani)

Critical edition and introduction by

Mahdi Ganjavi and Ali Mozafari Sirjani

With contributions by

Manochehr Bakhtiary and Ali Mozafari Sirjani

on the life and times of Foad Kermani and on the legacy of Azali discourse in the Constitutional Revolution,

and with a note by

Mehran Rad

ISBN: 9781997503309

The Azali discourse, which took shape after the death of the Báb and in opposition and competition with the Bahá’í religion, was not merely a religious movement. The Azalis sought to produce, from within the Islamic–Iranian tradition, an esoteric, anti-despotic, and reformist reading—one that on the one hand demanded a reworking of the Islamic tradition, and on the other sought to transform the foundations of religious authority by expanding the textual core and displacing established loci of authority. In this respect, the Azalis occupied an intermediary position, oscillating among three domains: mystical and esoteric tradition, modern rationality, and emancipatory thought.

The Azalis were well aware that openly expressing their beliefs in Qajar Iran would cost them their lives. For this reason, their writings assumed a dual character: an outward, exoteric layer and an inward, esoteric one. On the surface, they offered moral counsel and called for the ethical reform of society. At a deeper level, however, they pursued a critique of religious authority and the dissolution of the clerical institution, a critique of Islamic law and a call for its reconfiguration, as well as an invitation to struggle against the Qajar state.

This duality is clearly manifested in the works of Foād-e Kermānī, especially in Hayajān al-Vaṭan. At first glance, the language of the poetry appears nationalistic and declamatory; yet at a deeper level, it enters into dialogue with the thought and worldview of the Bábí movement and its social and political implications. Consequently, if the text is not read through a symbolic and code-conscious lens—one attentive to Azali allusions and the numerical calculations of words—it may be understood merely as a secular or Shiʿi reformist constitutionalist text, causing its distinct intellectual layers to be overlooked. Such oversight has plagued many readings of Azali beliefs and interpretations of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution.

Foad was a constitutionalist poet from Kerman, and since figures such as Mirza Aqa Khan, Shaykh Ahmad Ruhi, Mirza Reza, Majd al-Islam, and Nazem al-Islam emerged from this city, studying his poetry may be regarded as opening a window onto one of the major centers of the Iranian Constitutional Movement—namely, Kerman. Kerman in Foād’s time was a site of convergence for diverse ideas and beliefs, and can rightly be described as a vibrant workshop of theological thought: a city in which Shaykhis, Ismaʿilis, Neʿmatollahi Sufis, Bahá’ís, and Azalis were present, and through their interactions and conflicts over the relationship between the old and the new, articulated many of the concepts that would shape Iran’s future within this very sphere.

The present book, in addition to providing a rigorous and critical edition of this work, constitutes a conscious effort to rethink certain established narratives of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution. By offering a critically edited text and introducing its historical, intellectual, and social contexts, the volume seeks to move this work beyond a purely literary or local framework and situate it within the discursive struggles of the constitutional era. Alongside the critical edition and introduction, the book includes a collection of articles whose aim is not merely explanation or commentary, but analytical intervention in the understanding of constitutionalist discourse in Iran—an intervention that seeks to move away from the dominance of Tehran- and Tabriz-centered narratives and to foreground the role of the provinces, particularly Kerman, in the formation, continuity, and diversity of this movement.

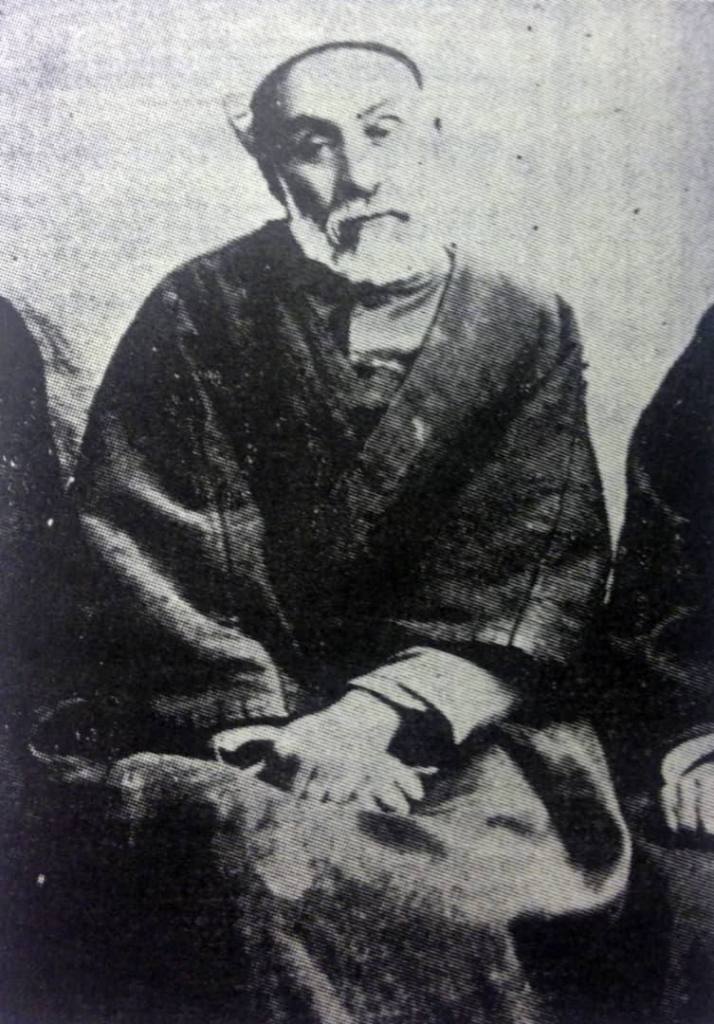

میرزا فتحالله قدسی کرمانی (فواد کرمانی)(۱۲۶۸ق – ۱۳۵۸ق / ۱۳۱۷ش)

میرزا فتحاللّه قدسیِ کرمانی، شاعر و آوازهخوان و نوازندهٔ تار، از سرانِ جامعهٔ اهلِ بیان (بابیانِ ازلی)، متخلّص به «فؤاد»، فرزندِ سلطانعلی، در کرمان متولّد و قریب ۹۰ سال عمر کرد. در فضای نهانزیستیِ بابیان، فؤاد از زمرهٔ شاعرانِ عارفمسلک و شیعهمذهب در منابعِ علنی معرّفی و شناخته شده است.

Mirza Fatolah Qudsi Kermani (Foad Kermani) (1268 AH – 1358 AH / 1317 SH)

Qodsī Kermānī—poet, vocalist, and player of the tār—was one of the leaders of the community of the People of the Bayān (the Azali Babis). Writing under the pen name “Foād,” he was the son of Solṭān-ʿAlī, born in Kerman, and lived to nearly ninety years of age. Within the context of the Babis’ clandestine mode of existence, Foād has been introduced and recognized in public sources as a mystically inclined poet and a Shiʿi believer.